250 years of American military ambition at sea

Today marks 250 years of the United States of America looking to the seas as a place to be a military and naval power.

It is generally accepted that the founding of England’s Royal Navy marked the starting point of military power at sea. Although England had a form of naval or maritime power and forces prior to King Henry VIII creating the ‘Council of Marine’ in 1546, which is commonly referred to later as the Admiralty, what is essential is that it made the future pathway for establishing standards and professionalism. In short, we combine professionalism with organisation as the founding principle of a military service.

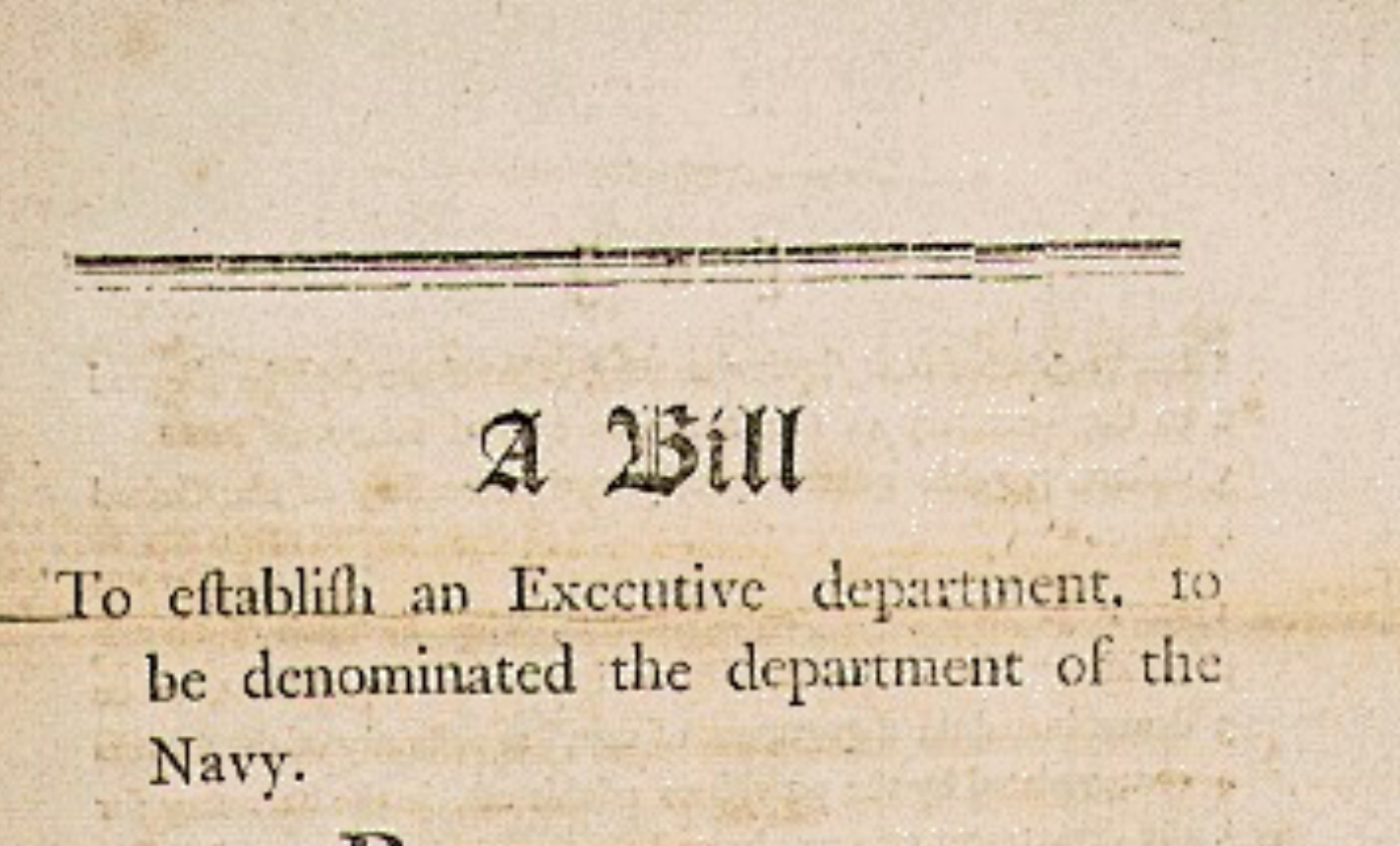

Following this accepted fact that has been in place for centuries, the US Department of the Navy, established on April 30, 1798, would continue to function in the same role in the story of American naval power, marking 227 years of service of the US Navy that we understand in its base form today. Although there is some wiggle room in this, as the US Navy was established on March 27, 1794, it is older; yet, the Department of Navy was not created by Congress until a few years later. Historians would counter that there is little difference between the revolutionary naval forces and the Continental Navy, and the US Navy of today. The fact that America did not sustain its naval force (1775-1785), and it had to be renewed in the period in which the creation of a Navy Department in the 1790s, instead makes the point that the US Navy of today and its forebear is no different from English maritime forces being distinct from the Royal Navy under King Henry VIII.

Either way, this nuance is important for many of today’s naval and sea powers, great and small, who have evolved with the times serving based on the geographical realities of which nation owns them. America is no different. For example, islands will always use seapower differently than that of great continental powers, even one like the US, which is flanked by two oceans; that mass of land can still undermine the best arguments of American naval power, rendering them subservient to concepts that erode the efficacy of sea power and maritime strategy.

American naval power, reaching its zenith during the Second World War, was a notable anomaly in reality, and demand forced America into action rather than an active choice. It stands distinctly alone compared to other periods in the history of the US Navy, a path that other navies––which are not islands––, such as European navies, have taken. By the end of 1945, America’s navy was viewed as coming of age. Its success in the Pacific theatre of World War Two was immortalised. In my 2021 PhD thesis and forthcoming title, I argued that this was ‘America’s Campaign of Trafalgar.’ It began with the Battle of Midway in 1942 and continued through to the Battle of Leyte Gulf in 1944. These victories, including that of the US Marine Corps, became central to the US Navy’s self-confidence and its place in the broader national identity as the navy looked to establish a prominent role in postwar national defence.

Nevertheless, it was short-lived, as debates over the US Navy and defense organization took place post-war. In Washington, D.C., the politics of defence, with deep roots, made it appear that by 1946, the US Navy had done very little in wartime. In reality, the aspiration of many Americans and US naval personnel to surpass the Royal Navy had ended in disaster as they turned their backs on what they should never have lost sight of, which was the vulnerability of a naval power answering to a continental country where the minds of land-thinkers dominate. This struggle has not changed since, and in 2025 only deepened.

Either way, at 250 years of America’s military power at sea, it is a choice to go to sea, something that many Americans and those who support US naval power often forget. A choice can also turn into a choice not to. That should be the message at this juncture.