A Corbettian Navy through Strategic Necessity

Guest article by Dr Mark Bailey RAN. It reflects on my article on British seablindness, the importance of seapower to island states and the current situation with the Australian and Japanese navies.

With respect to the Royal Navy (RN), Dr James W.E. Smith has noted that:

“The answer to “What is the navy for?” should have been thrashed out and resolved long ago; it was an easy task for the answers lay in the past, and from that, the answer communicated full volume to those at the highest level of decision-making in the nation. That this was left to linger by some past generations has caused turmoil that cannot be overlooked, particularly by those who present nothing but a negative message about the navy who had an opportunity prior to do something to avoid the situation the service now finds itself.”

Australia has a history of ignoring its maritime history, and for 50 years review after review has called for a larger Navy to ‘defend Australia’s maritime interests’.1 This was at best a partial understanding of Australian requirements, for the Australian Government and people have never had a genuine understanding of what it means to be a maritime nation. Current developments are remarkable in that an outcome has been reached which is in accordance with the principles of maritime strategy by Sir Julian Corbett (1854-1922). Yet, there is little understanding in Australia of Corbett’s philosophy of Seapower and maritime strategy among government and the Royal Australian Navy (RAN).2

What has driven this Corbettian outcome is Australian strategic realities at a time in history when the second globalisation is collapsing and the world is assuming a strategic shape reminiscent of the 19th century. Australia has taken a step forward by acknowledging the realities of our geographical position in the world-ocean and of the strategic circumstances of a pure island Seapower which is reliant on maritime trade for its existence. This has resulted from the eight-month Defence Strategic Review, the five-month independent analysis of the surface fleet and four months of government deliberation before its release.3

Australia has developed these plans based on analysing geostrategic realities. The matter explored here is how this outcome validates the fundamental verities of Corbett’s philosophy of Seapower and exposes the intellectual and strategic bankruptcy of both navalism and continentalism. Britain can be used as a comparator here, being the leading example of a pure island Seapower state which abandoned maritime strategy and attempted to turn itself into a continental power,4 making itself globally irrelevant in doing so. The dismal failure of this ahistorical effort is widely observed in Asia.

The Australian effort is not to be lauded at its current stage, for Australia has been here before. The 1987 Defence White Paper agreed to an increase of the surface force, but it led to no significant results.

In this theatre (which the US has designated USINDOPACOM or US Indo-Pacific Command) it is critical to recall the issue of scale. Here, the South China Sea (about half of which is abyssal deeps) is small at just 1,420,000 square nautical miles. By comparison, the North Sea is a carpark puddle of just 290,000 square miles. Indonesia is 735,000 square miles (76% water) with around 280 million people and the 7th largest economy in the world (about US$4.7 trillion). Indonesia dwarfs the largest western European country, France (210,000 square miles, 68 million people, US$3.1 trillion). These issues of scale are stressed because in the author’s experience presenting at conferences in Europe over the last decade indicates that most Europeans have no idea of these realities.

Scale matters because it structures strategic responses.5

With the public release of the Australian Defence Strategic Review (DSR) in 20236 and now the release of the RAN Enhanced Lethality Surface Combatant Fleet: Independent Analysis of Navy’s Surface Combatant Fleet (henceforth the Surface Fleet Review) the shape of Australian strategic thinking is clear.7 Under current plans, the Australian ‘focussed force’ to address the potential outbreak of a ‘Pacific War Mark II’ has two parts:

Offensive Strike. The first focus of the DSR is on joint offensive capabilities built around eight SSN and sophisticated capability for long-range land-based joint fires. The latter is composed of land-based long-range tactical ballistic missile systems and air-launched missiles. A sea-based long range fires capability based on Tomahawk SLCM will complement this. Of special note with long-ranged systems is the highly complex problem of obtaining, assessing, developing and integrating data to build the kill-chains required, especially against mobile maritime targets dispersed across vast areas of open ocean, island chains and archipelagic regions.

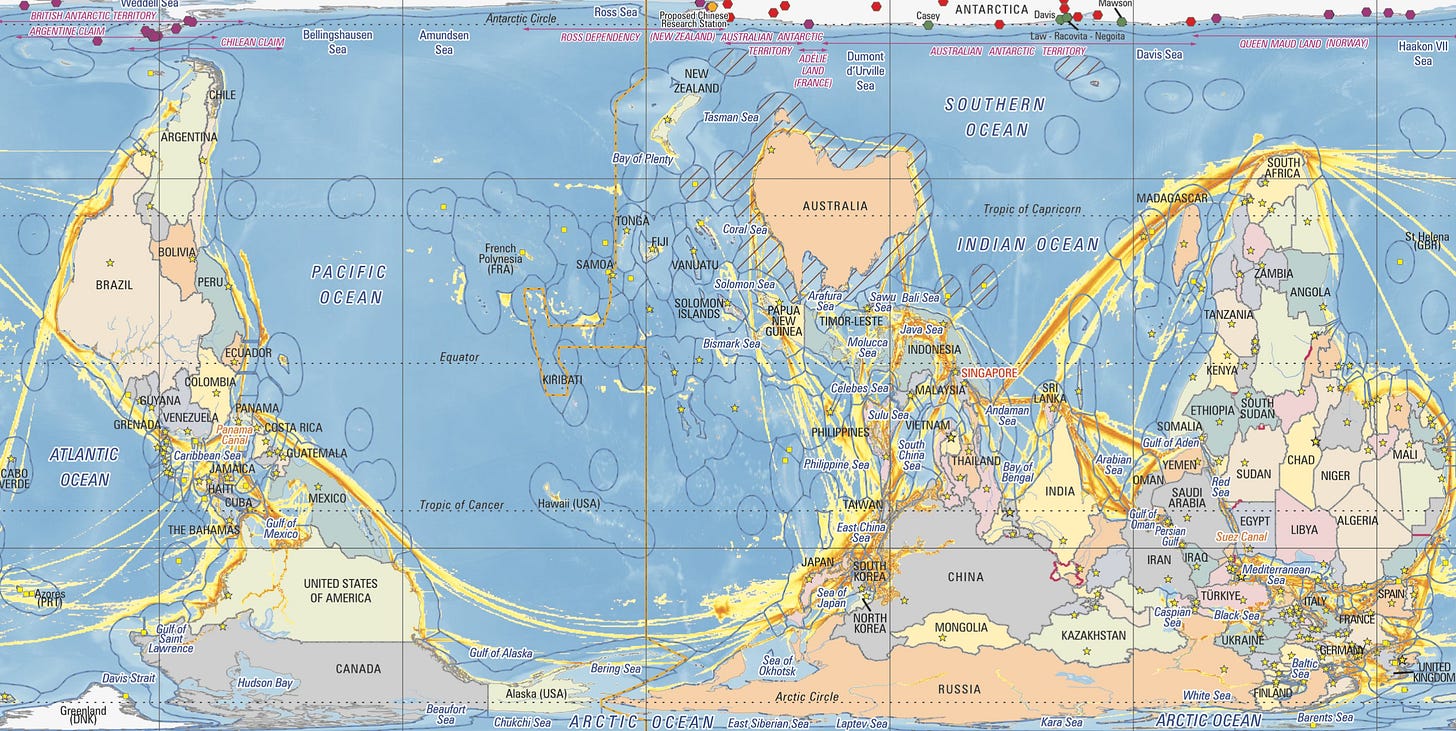

Note carefully that the Australian DSR and public assessments define this capability as domain-based rather than service-based. Australia has moved over many decades through the lessons of ‘jointery’ to arrive at a domain, effects-based philosophy of war. 8 None of the five domains (maritime, land, air, space, cyber) are controlled by single-service concerns. The map below explains why. Australia sits in the middle of the world-ocean, which is comprised of the immense Southern, Indian and Pacific Oceans. The island-continent itself sits in Oceania, at the end of a vast pattern of islands controlled by thalassic nations and shot through with a filigree of maritime trade routes. The global demographic and industrial heartland borders the world-ocean. Through this perceptive lens, continental Europe is revealed as aa remote, rather minor place, connected as shown by maritime trade: yet Britain is not as minor as Europe itself, for it too depends on that same maritime trade and is less insular in outlook.

Maritime Trade Protection. The second focus of the DSR is the maritime trade protection capability. This will be composed of three Aegis Baseline 9 air warfare destroyers (which are a light destroyer or large frigate compared to Japanese and Korean equivalents), six Aegis-fitted ASW frigates (a variant of an ASW destroyer) and 11 general-purpose frigates. There is then a modest power projection capability built around three large amphibious ships, and a substantial constabulary and regional stabilisation force. While this force is capable of contributions to US efforts in a modern version of the Pacific War of 1941-45, a cursory examination of that war shows immediately what Australia’s critical contribution actually is. Just as in 1941-45, Australia provides strategic depth and a secure rear logistics and support area where US forces can initially deploy to, train and acclimatise before moving forward. That said, technology has permitted the use of Australian bases for long-ranged US strikes against the Chinese periphery, but even this has close 1941-45 parallels. During that conflict the major Australian military role was using its forces to secure the maritime supply and trade routes between Australia and the USA via Hawaii, the Panama Canal and Cape of Good Hope. As neither geography of the overall strategic shape of such a conflict has changed and cargoes still move in slow monohull merchant ships, the same role can be forecast for any future conflict. The Surface Fleet Review merely reflects this maritime reality, and even a cursory examination of Corbett confirms that it is indeed valid to do so.

Australia in the World-Ocean

As the Australian Strategic Policy Institute noted:9 ‘Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles announced that Navy’s future surface combatant fleet will comprise:

Three Hobart class air warfare destroyers with upgraded air defence and strike capabilities

Six Hunter class frigates to boost Navy’s undersea warfare and strike capabilities

Eleven new general purpose frigates that will provide maritime and land strike, air defence and escort capabilities

Six new large optionally crewed surface vessels (LOSVs) to significantly increase Navy’s long-range strike capacity

Six remaining Anzac class frigates with the two oldest ships to be decommissioned as per their planned service life

25 minor war vessels to contribute to civil maritime security operations, which includes six offshore patrol vessels (OPVs).’

Four MCMV may be retained but this is uncertain at this stage.

By comparison, the current RN strength (ignoring its SSBN force) is six SSN, two carriers, two large amphibious ships, six air-warfare destroyers, 11 general-purpose frigates, 25 constabulary vessels and seven MCMV.

It is a monument to the disastrous philosophical victory of continentalism in Britain and the resulting systemic failures of the RN and UK government over the last 60 years that it has been reduced to the point where a medium power like Australia can plan to match it in military capability. A more revealing comparison to the current state of British naval capability is to compare Britain to her peer pure-island seapower: Japan. The Japanese Maritime Self Defence Force (JMSDF) simply outmatches the RN in every regard. The JMSDF has 23 conventional submarines, four light carriers, three large amphibious ships, 10 Aegis fitted AAW destroyers, 36 general purpose frigates (six pending retirement but with more capable replacements planned), 22 MCMV and six constabulary vessels. Japan’s future plans are to expand this force. Now, ‘hull counting’ surely is a navalist forte. This is why it is deliberately used here, to illustrate that the philosophy espoused at organisations such as Joint Services Command and Staff College, Shrivenham (if continentalism applied to an island-nation can even be so described) has failed Britain, and failed catastrophically. No appeal is made here to past glories: the failure is that a maritime-trade-dependent pure island state now lacks the seapower it requires to exist in a rapidly deglobalising world, let alone to prosper in it. The British focus on continentalist philosophies has created an existential threat to the country. It is very difficult to fail more severely than this in peacetime.10

By comparison––and noting that this is an approved plan and not yet a written-in-hulls reality––the Australian plan is arguably both more balanced than the current RN and is more attuned in the direction of Corbettian realities of being a pure island-state Seapower. The outcome is a hard-eyed Corbettian response which was arrived at not by looking at Corbett’s philosophy of Seapower: because the RAN has also forgotten that but instead organically developed by looking at the straightforward geographic and strategic realities of a possible ‘Pacific War Mark II, China Reprise.’11 It is based instead on years of solid consideration and experimentation within defence and on the simple reality of Australia being a pure, island seapower entirely dependent on maritime trade.

If nothing else, this proves the profound philosophical validity of Corbett’s philosophies of Seapower. It also starkly illustrates the profound failure of continentalist philosophies when they are applied to seapower states.

Britain is unarguably a pure, island Seapower state entirely dependent on maritime trade. Most unfortunately, however there is insufficient evidence that the RN itself understands this point let alone the British Government where a complete collapse in education on seapower has occurred. Both have been aided and abetted in this ignorance by the continued failed continentalist views visible in the outputs of military establishments and the British Government.

How this occurred can now be understood, having been revealed by Dr James W.E. Smith’s completed PhD research. The UK had the dubious ‘era of long peace in a globalised world’, giving the illusion it can abandon seapower, something it had never done prior and instead became a ‘bargain-basement’, small, irrelevant continental power. As human beings live on the land and only depend on the sea, they understand land matters such as continentalism intuitively. Australians are of course no different. Yet from the Australian perspective, what cannot be understood is why the British ignoring of Seapower continues in a world where the Second Globalisation is clearly collapsing and the overall strategic shape of the post-first-globalisation world (1919-39) is re-emerging. Worse, it is re-emerging in a global strategic framework which more closely resembles the 19th century than the inter-war era.

Since 1945 the RAN and the RN both clearly understood and commonly practised navalism, the policy of maintaining naval interests. The RAN disconnected from the RN because the British withdrew from their commitments east of Suez. The British withdrew from engagement in the more distant parts of the world-ocean as the USN was maturing its global maritime dominance. The US also became willing to share advanced naval technologies with the RAN, which aided the separation.12 The RN should not have permitted the depth of distance which eventually occurred between it and the other (including former) White Ensign navies around the world.

This is not an entirely acceptable attitude for the naval and military officers of island states dependent on maritime trade. Navalism itself was the creation of continental states with naval interests, in particular Imperial Germany and the 19th century United States and France.13 Yet, it is also a natural attitude of professional naval officers who focus on ships and tactics; warfighting matters, while generally remaining ignorant of what navies are actually for; the strategy of employment of maritime forces in the national interest. Few ask: why the exclusive focus on fighting a peer competitor at sea (all know this is important), when most of what a navy does is peacetime tasking to build and secure that same peace? Navies exist to deter or prevent war and secure maritime trade in all its aspects from cargo import and export to seabed mining of hydrocarbons and other resources. There is a plethora of peacetime tasks associated with achieving these ends. Being able to fight a war is critical to those two primary maritime functions because it helps to prevent war. It is important to understand the relativities of effort here. For example, the Falklands War was the last high-intensity war the RN was involved in. It lasted from 2 April to 14 June 1982, or 2 months, 1 week and 5 days. Let us assume six months including the buildup and rundown periods. That is about 0.5 of a year of the 42 years since its outbreak, or about 1.2% of the time-span.

Therefore, about 98.8% of the RN’s time since has been focussed on Corbettian, maritime peace-making tasks: those Seapower tasks of critical direct value to the nation. Exactly the same is true of the RAN which, when coordinated with whole-of-Government intent, has demonstrably become good at conducting these peace-making tasks. These include sealing Australian maritime borders from illegal immigration by sea, protecting fisheries and the vast Australian offshore oil and gas industry, maintaining regional stability, protecting maritime trade, opposing Chinese efforts at regional influence-development, reinforcing and deepening relations with ASEAN and building the trust necessary for the development of new relationships with regional powers including India and Japan.14 New alliances which actively deter possible PRC adventurism are developing from these activities – a strategic-level pay-off and one which is fully in accord with Corbett’s philosophy of Seapower.

Where Australia has been remiss to date is in not funding the five Domain capabilities discussed above to succeed in deterrence of major regional powers with hostile intent. The DSR and Surface Fleet Review are clear responses to this.

Nothing about this is new to the RN, which has been in the same situation before, most notably in the last decades of the last long peace of 1815-1914. The RN could look back to Sir John Fisher’s (1841-1920) reforms here, in some ways. Those reforms were Corbettian – deter war, build the peace, protect the national maritime trade-based economy. Professor Andrew Lambert’s tour-de-force study on just how the British had their own way of war examines this and also leaves the current government and RN nowhere to hide in philosophy of Seapower terms.15 Smith’s research that covers what has occurred post-1945, is equally important and just as intellectually pitiless in that it leaves the RN and UK government nowhere to stand on their handling of the needs of a Seapower state over the last 50 years. Just like Australia, the maritime components of the British military and Government agencies across the five Domains are by far the most important to that nation. As a Service, the RN should be focussed on peace-building for its deterrence value, and maritime trade protection for national survival reasons. Yet to do that, the British defence establishment has to recognise, and then abandon, its self-inflicted and failed continentalist-oriented philosophy of those fifty years. It will be exceptionally difficult for the people currently forming the system to even admit these failures (let alone make the needed corrections) as these philosophies formed their world-views. Yet on the positive, Lambert and Smith have done the work, but if the British Government or RN is engaging with them is an open question.

This is all ‘common sense’ in Corbettian, terms, and aligns conceptually to the strategic plans Fisher developed 110 years ago. This understanding used to be innate, intuitive knowledge in the RN, whereas it never was in the RAN or in Australia generally. What the Australian example demonstrates is that even lacking understanding of Corbett at all, a national strategy based on meeting quantifiable strategic threats in a maritime theatre is fully aligned to Corbett’s philosophy of Seapower. In turn this unambiguously further illustrates, as Smith has researched, the comprehensive failure of, and the intellectual bankruptcy of those continentalists who destroyed Britain’s Corbett-based way of war after 1964, and of their successors.

The contents of this article are Dr MarkBailey’s personal views and in no way whatsoever reflect the views of the Royal Australian Navy or any agency, section or element of the Australian government. They are based entirely on Dr Bailey’s personal academic research, historical observations in relation to the protection of maritime trade, and personal experiences and understanding of Asian and Oceanian maritime history. All references to current events are drawn from public sources.

Dr Mark Bailey completed his Doctorate at the Australian Defence Force Academy in 2019 (thesis title ‘The Strategic and Trade Protection Implications of Anglo-Australian Maritime Trade 1885-1942’. He is a serving officer in the Royal Australian Navy, and a member Australian Naval Institute and ADFA Naval Studies Group.

NB from James: I am very grateful to Dr Bailey for writing this article which also presented feedback and a perspective from another island nation to my comments on British seablindness (see https://www.jameswesmith.space/p/seablindness-and-the-royal-navy-today) Bar some editorial input from myself, the content is entirely originally his.

The word ‘Seapower’ is capitalised as a proper noun here because is refers specifically to term in Corbett’s definition, as the totality of the maritime, naval and economic aspects of the state. Where not capitalised, it carries the more modern, navalist meaning, ‘a nation having significant naval strength’.

Enhanced Lethality Surface Combatant Fleet: Independent Analysis of Navy’s Surface Combatant Fleet, Commonwealth of Australia 2024.

James W.E. Smith “Deconstructing the Seapower State: Britain, America and Defence Unification” PhD thesis., (King’s College London, 2021).

During Exercise Kangaroo 1992, where the author was on exercise control staff, NATO observers were astounded to be briefed that one battalion area of operation was larger than Belgium.

National Defence: Defence Strategic Review, Commonwealth of Australia, 2023

Enhanced Lethality Surface Combatant Fleet: Independent Analysis of Navy’s Surface Combatant Fleet, Commonwealth of Australia 202

The oldest primary source reference available to the author regarding an Australian Joint Force Headquarters in the modern sense of the term has been found in ACB0347 (1970) Mobilisation of Naval Personnel p.15-5, where additional manpower for Australian Joint Force Headquarters Darwin is noted.

See, Smith “Deconstructing the Seapower State: Britain, America and Defence Unification” and his forthcoming title.

A possible conflict to be deterred. An ASPI Report on escalation risks is available here: https://www.aspi.org.au/report/escalation-risks-indo-pacific-review-practitioners

Shackleton, D., (VADM retd) Sea Power Series: The Impact of the Charles F. Adams Class Guided Missile Destroyers on the Royal Australian Navy, https://www.navy.gov.au/media-room/publications/sea-power-series-05. These ships were more advanced than their RN equivalents, the now decommissioned County class.

No criticism of Mahan is meant or intended here. While more a navalist philosopher than a philosopher of maritime Seapower he had a specific political-strategic intent; to influence the USA of his era to take its maritime interests more seriously. In this case, his navalist approach was a tool used in public discussion and debate to obtain a maritime strategic intent. As Dr K. McCranie demonstrates in his remarkable comparative study, Mahan, Corbett and the Foundations of Naval Thought, (US Naval Institute Press, 2021) Mahan and Corbett were complementary, grounding their work in historical examples and using theory to derive applications from those examples to suit present-day applications.

Lambert, A., The British Way of War Julian Corbett and the Battle for a National Strategy. Yale University Press, 2021.