Same Old Same with the British Army?

The British Army's message of January 2024 fell flat but it did tell us something about how land-centric thinking still dominates British defence.

Early in 2024, the most senior leadership of the British Army argued that Britain needs to be put on a ‘pre-war’ footing, in particular due to the “threat that Russia possess”,1 even as far as a potential ‘World War Three’ situation.2 It’s not new for outgoing army generals to poke some criticism at the Government, for any other time would be a breach of civil-military relations resulting in a polite but immediate demand for their resignation, but there was far more to this than met the eye.

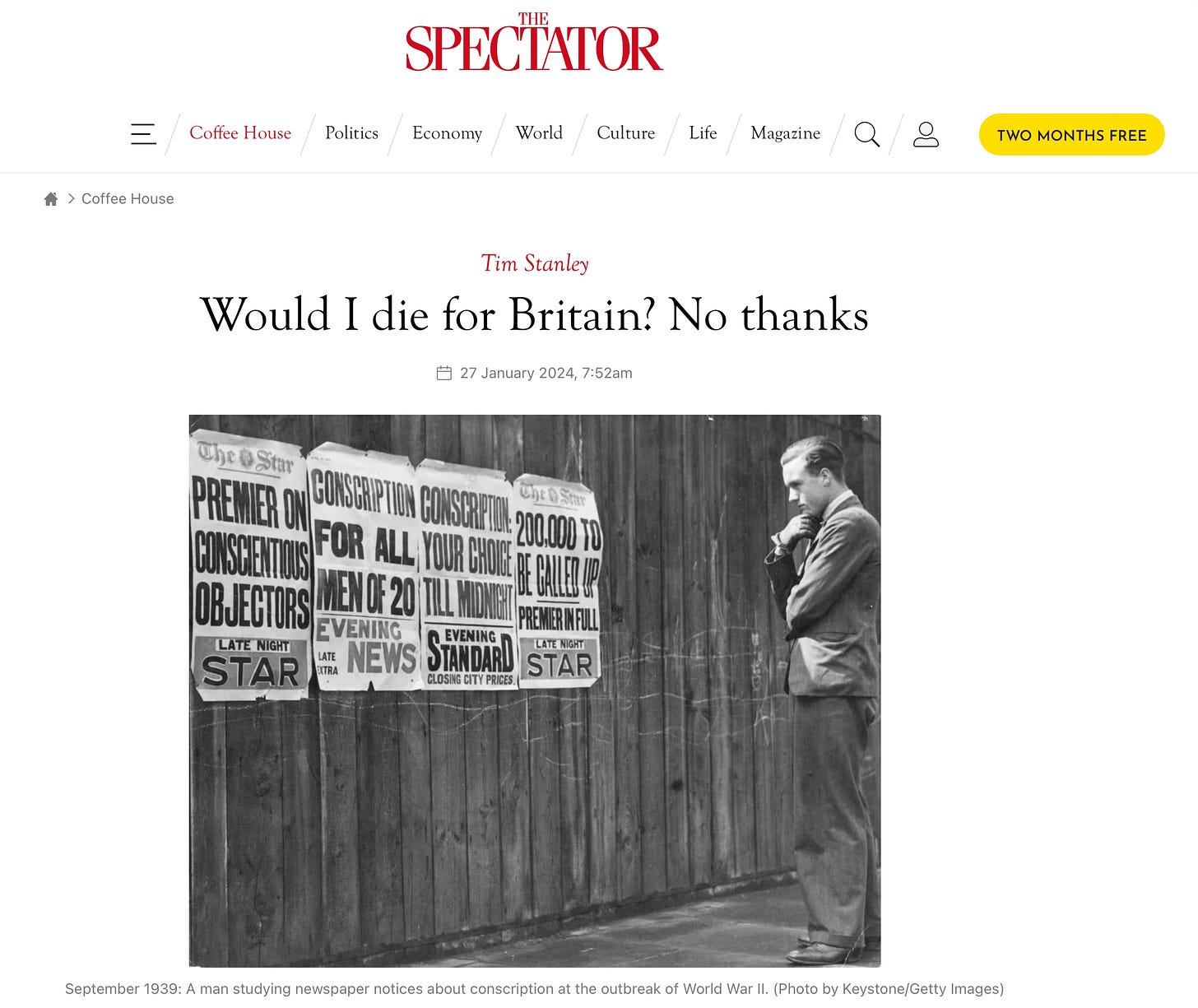

Whatever the intent of senior Army leadership was, it spectacularly backfired with the media starting a public debate,3 if not a minor societal panic, towards public conscription and stoking some misguided notion of past world wars towards a new one, even if the Cold War has renewed itself. Sadly, the opportunity for a 1940's style Marshall plan in the 1990s to help bring Russia into the Western fold, protecting their national pride while providing the Russian people with just a sliver of hope for democracy––the last taken from them in the early 20th century––has been lost to time. Instead of a discussion on the state of world affairs and how British defence would address it, their efforts had a very different result than the army intended. If it was the army’s objective to ask for more soldiers then that message was lost in translation. Instead, the national discussion, particularly in the media, became one of why a call up for ‘King and Country’4 would be rejected by many of the British public with many stating that only what they perceive as a direct threat to the homeland will motivate them to consider it. This was leading to the most dangerous question that army and Royal Air Force (RAF) leadership have wanted to avoid after the 1950s: what are the nation's vulnerabilities?

A large Russian military force charging across the Rhine, particularly after the development of the nuclear deterrent by sea, was as misguided immediate threat to British soil then as it is now, likewise with that of invasion––something the Army and RAF admitted to the Admiralty in the 1950's only to be buried later as it did not serve their narrative of historic events and that to acquire future funding. Therefore, if defence of their homes is the only benchmark for British citizens to consider joining the Armed Forces––the ghosts of foreign policy in the Middle East loom large over Government and the British army alike––it is not a large army in support of a land war they would be scrutinising. Instead, the geographic realty of being an island and threats from the sea that could knock Britain out of the game to support European allies, let alone the quality of life British citizens have become accustomed to with the open flow of goods and resources. These facts being exposed would have deepened the headache for Generals if the dots were joined together to reach the conclusion that protecting Britain is a maritme conversation not a land-centric one––something once known. Without useful maritime messaging and a functioning naval public relations system in Whitehall––lost with the abolition of the Admiralty5––senior land-centric minded leadership (military and civilian) managed to continue the trend of post-1945 that British national defence is served best by ‘being in Europe’. Futhermore, perhaps if the education of British national identity, geographic realities, history and sense of cultrual nationality had not been eroded, then such a call would have mobilised the quality of debate to focus on an increasingly gloomy world situation and how Britain is vulnerable to it.

There is an element of ridicule aimed at the army along similar lines to a Gilbert and Sullivan play. "I am very model of a modern major-General” springs to mind. 6

The army’s comments fit within a trend with deep historical roots that extend back over centuries. The army has overemphasised the risk of invasion––something they knew the Royal Navy would Britain from––and importance of a massive land war with a ‘bogey man’ every time it felt its fortunes slipping away or the attention of Government officials center on another military service. The invasion fears that army officers spread after 1805 through into the 1900s were exactly that, an attempt to distract from those communicating national realities. For island nations, geographic realties mean the first and last defence of Britain is always its navy and if the Navy is incapable of defending home soil, the correct response is to make the Navy bigger and better.

But arguably, the Army has not learned what its forebears understood, such as the Duke of Wellington (1769-1852)––who seemingly knew a lot more about how a small nation with few resources surrounded by the sea was venerable to defeat–– that the Royal Navy (RN) and seapower is essential for the Army to work with, not against, even in the corridors of the Treasury. Actively modelling the Army into a similar form of continental army will result in a bungled service, subpar at most things and likely incapable of performing its mission simply because the nation can’t afford to build and maintain a vast army with an air force at the same time as a navy. This would lead to a futile stand against the army of a continental nation and even if only employed as a delaying action against them would result in a unacceptable risk to life and equipment at the cost of the other services being able to do their tasks. In the case of the Royal Navy, cutting something like Anti-Submarine Warfare equipment to fund a vast army would endanger shipping and potentially starve Britain out of war or conflict.

For a few brief moments in the 1950's, the British Army started to realise that aligning itself with the RAF––who were only interested in presenting to the Government that the only option is to ‘bomb the way out of every foreign policy problem’ and therefore there's no need for a navy––and the idea of Britain as a great power in Europe was fool hardy. But that alignment was short-lived. Instead, the result was a British Army on the Rhine (BAOR) that could not hold up against Soviet attack, quite possibly forcing the Royal Navy and merchant sailors to rescue them from the Continent, 1940 Dunkirk style––if even possible. It was this distorted vision that placed an army at the heart of an island over that of a navy––which naturally gained RAF support for together they could outnumber the Royal Navy in any debate with the Treasury and Government officials––that twisted and discard British strategic experience. Where maritime strategy was once at the core of national defence strategy, it was replaced by the misguided idea of a grand land war, something supported by a Ministry of Defence designed think in European land-centric Prussian style war terms, not facing threats by using Britain’s strengths and expereince. It is this culture that reigns supreme today and is exposed in the Army's words of January 2024.

Solders indoctrinated to this continental way or thinking, or those retired who believe in it, are dreaming of First World War trenches, the BAOR and grand land campaigns akin to the Duke of Marlborough (1650-1722) rather than the reality of what made the British Army highly respected: a surgical blade to be used with pin-point precision around the world to back up allied continental armies. The relationship with the Navy is critical to this, something the Duke of Wellington knew: that it is seapower and logistics by sea that put and kept his army in the Peninsular War (1808-1814) and placed it on the field of Waterloo (1815) to support Europeans in the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1810) and his continental army. For every solider in the field under the command of the British Army, numbers of British sailors had put them there.

For every solider in the field under the command of the British Army, numbers of British sailors had put them there.

France of the revolutionary wars and Napoleonic period (1792-1815) along with Russia, especially if properly managed today, have deep pockets of resources, making the idea that an island nation’s army could defeat a determined continental land force as farcical and fantastical as it’s always been, particularly if that army comes at the cost of resources for the Navy.

While generals have started spreading the same old message again in 2024, the Royal Navy could be found actively engaged in combat operations defending sea trade––of which Britain is first and foremost vulnerable to––with a fleet that is increasingly criticised for its inability to execute its core mission. It reminds us of the disparty not just between Army and Navy over national defence strategy but that it has always been the few in the Army that understood what the function of it is in defence of an island nation.

UK citizen army: Preparing the 'pre-war generation' for conflict, BBC, 25th January 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-68097048

NATO warns of potential all-out war with Russia, NATO, 18 January 2024, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_221779.html

Public face call-up if we go to war, military chief warns, Daily Telegraph, 23 January 2024, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2024/01/23/public-call-up-army-too-small/

Would I die for Britain? No thanks, The Spectator, 27 January 2024, https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/would-i-die-for-britain-no-thanks/

James WE Smith “Deconstructing the Seapower State: Britain, America and Defence Unification 1945-1964,” PhD thesis., (King’s College London, 2021).

"I Am the Very Model of a Modern Major-General" (often referred to as the "Major-General's Song" or "Modern Major-General's Song") is from Gilbert and Sullivan's 1879 comic opera-play The Pirates of Penzance.