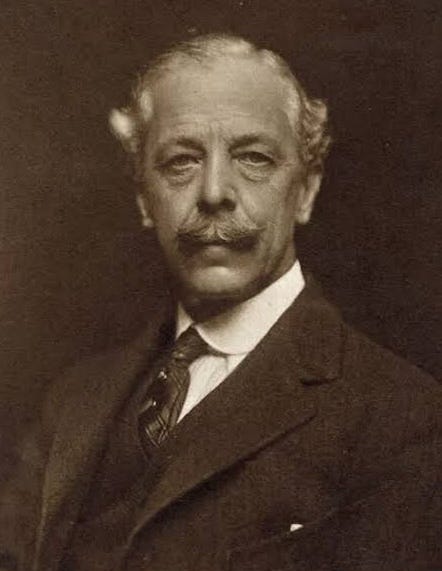

Sir Julian Corbett and Maritime Strategy at 100: A Long Hard Look in the Mirror

A century after the death for Sir Julian Corbett, I reflected on the implications of Corbett’s maritime strategic thought for Britain’s evolving defence role, and raised some hard questions.

This paper first featured for The Naval Review Journal in 2022 to mark the centenary of the death of historian and philospher of seapower and maritime strategy, Sir Julian Corbett.

The editor of The Naval Review remarked:

As part of the Corbett 100 series, revisiting the career and influence of Sir Julian Corbett a century after his death, the author reflects on the implications of Corbett’s maritime strategic thought for Britain’s evolving defence role, and raises some hard questions policy-makers and naval professionals alike should consider carefully.

The following is a special edition of that paper for my substack.

A century ago, in 1922, arguably Britain’s last great national strategic thinker, naval historian and philosopher of seapower and maritime strategy died. Today, Julian Corbett and his scholarship offer insight for the Navy, and broader military and policy-makers, when addressing the realities of national strategy. Contemporary scholars and academics have discussed the relevance of many of Corbett’s insights.1By using Corbett’s methodology – the analysis of trends and experience of history – on the legacy of his influence, we can find wisdom, signs and portents relevant both today and tomorrow for the naval professional and beyond.

Corbett’s life was cut short; by 1921 he was preparing to discuss the future of British defence strategy which included the end of Empire while addressing high-profile issues at the time, such as Army-Navy cooperation in the First World War. For Corbett, it was less about what had gone wrong with British strategy in the First World War but, at least from Corbett’s maritime perspective, what should have happened. The near-disaster at sea that may have resulted in national starvation due to British shipping being under sustained U-boat attack, and the debate over the conduct of the 1916 Battle of Jutland, both concerned Corbett. This concern was not just of rampant and sentimental navalism getting out of control but how the resulting ‘finger pointing’ would become entangled with the British Army’s deflection from the greater disaster that had resulted from the large-scale commitment of men and resources to the Continent. This action alone had destroyed Corbett’s efforts towards understanding of a national strategy that he had researched, taught, and communicated to decision-makers by 1911.2

By 1921 his thoughts had turned to a fundamental issue at the heart of British defence and how to address it: what could happen if the uprooting and discarding of strategic experience were prioritised because kneejerk reactionary responses to prevailing political winds and recent short-term tactical problems were favoured? Unfortunately, he was never able to address this problem. The path to continentalism, which rejected all British strategic experience in which the Royal Navy was fundamentally interlinked, was left ajar, left to the responsibility of the Admiralty and later generations to address.

The Admiralty’s permanence of its residency in Whitehall symbolised its durability, adaptability, and pre-eminence amongst the service ministries. Its age was reflected in its experience of traditionally attempting to anticipate changes in the environment that the Navy faced, while developing capabilities that allowed the organisation to continue to thrive under new and different circumstances. The lack of a distinct separation of civil and military hierarchy in the Admiralty emphasised a critical point that Corbett had researched in his analyses of Britain’s national strategic experience over prior centuries that had resulted in the decision to emphasise an unnatural environment for humans – the sea – exerting effort towards developing strategic power to project influence beyond the limits of a resource poor island.

The message of sea dependency, why maritime strategy only works for Britain, and other points, became intertwined and dependent on the Admiralty being able to communicate it. To some degree, the Admiralty was as much a development of the requirement for the Navy to be able to communicate its message as much as it was to command and control the Naval Service. Its higher calling was to guard strategic experience, and the lesson that national strategy should take precedence over the whims of overexcited thinkers and technologists who could only offer assumptions, guesswork and theory.3 These thinkers who offered little beyond unproven theories had the advantage of responding to ‘what was topical, shiny and new’ to politicians. In contrast, those like Corbett had the leverage of being able to, with confidence, evidence what had worked successfully and repeatedly before.

However, to do so requires an ever-present, repeated, clear, coherent message that interprets often complex strategic concepts and naval theory into something the political decision-makers can understand. It is foolish to believe the politician or civil servants naturally understands strategy, security, sea dependency or seapower. They must be educated repeatedly. This is not just an issue in the past but a problem today.

Although Corbett had studied the actions on land and sea of England and later, the U.K., that had ranged from the exploits of Sir Francis Drake (1540-1596) versus the Spanish Armada in 1588 through to the development of the ultimate fighting sea-professionals like Lord Horatio Nelson (1758-1805), Captain Edward Pellew (1757-1833) and Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood (1748-1810) and notwithstanding that of the Royal Marines, it was not debating past historical events that concerned him. Corbett’s concern in 1921 was that, so often, the understanding of seapower and its role in national strategy relied on stories of duty and sacrifice, which only furthered the problem because naval operations were far over the horizon and challenging to demonstrate to politicians and Treasury officials. Ultimately, he believed and proved that the Naval officer and the Royal Navy were doing precisely what they were in fact best at doing; being the ultimate sea professionals and continually getting on with tasks assigned to them by the state. Guarding national strategic experience was a task for Admiralty civil servants and, like Corbett, the historians who could influence debate and educate the critical individuals beyond the confines and limitations of being a servant of the state. It was a critical symbiotic relationship between civilian and naval officer, and likewise, national strategy demanded that the Services work together rather than being homogenised into anti-intellectuals. Corbett believed in those who saw advancing their intellectual development as symbiotic or in partnership with the professional tasks required of them.

In reality, the fact that the Admiralty was civilian dominated underlined that Naval officers were inferior – if not outright sometimes dangerous – at communicating what strategy was or even what the Navy was for. This was entirely different for Army and later Air Force personnel, who were simply ashore more often and therefore able to stay in contact and influence decision-making networks while staying in step with the political and social direction of travel; the Naval officer rarely had the opportunity to do so. This only underlined that individuals, Corbett included, were vital to the debate to ensure maritime strategy, and its experience, was included in national discourse on strategy and defence policy. Army or Air Force personnel, often backed by more extreme ‘domain and power’ theorists, sought to glorify extended land operations, which were alien to British strategic experience and represented continentalist approaches. They often attempted to prop up theory with some valiant cause or misguided need for another Battle of Waterloo-style engagement. At the same time, after 1945, air power concepts in place of national strategy were promulgated by extreme air power theorists who used the one-off air battle, the so-called ‘Battle of Britain’, to bolster public and political appeal for their concepts. It was little different to, as Corbett knew, navalists who ran away to the Battle of Trafalgar when the political winds strengthened against the Royal Navy.

The Admiralty was the cathedral to British strategic experience and British seapower, adjoined by Britannia’s own master of fighting at sea, Lord Nelson on his column. By comparison, the construction in the United States of the ‘Pentagon’ symbolized the very pinnacle of continentalist Prussian/German ideas of war. The British tradition of maintaining peace and avoiding total war at all costs was driven by harsh national realities. Corbett’s recognition that classical strategic theory, long dominated by continental military concerns, conflicted with his analyses of unique British experience dating back to the 1500s. The Second World War saw this experience ignored in the many decades that followed. Guarding and educating about strategic experience was vital; Winston Churchill made the point when he so fatefully in the summer of 1914 encouraged a mass army commitment to Europe. In the broadest sense, losing experience and knowledge of maritime strategy was only ever a few steps away or, as was the case with national strategy, from a continentalist throwing it all away. The worst possible outcome is that one particular theory, one tactical experience or technology, would be used as a battering ram and that everything known yesterday would be seemingly forgotten the day after.

It was no coincidence that maritime strategy within the framework of national strategy was lost – or purposefully discarded – by 1964 with the creation of the Ministry of Defence. Maintaining institutional knowledge and passing that experience from one generation of civilian and military professionals to the next became challenging to maintain within the process of such a fundamental change and the raft of changes that occurred in defence and Britain after 1945. The traumatic experience of 1939-1945 and its conclusion with atomic bombs provided a handy wedge for those who wanted to reset the clock on strategic experience. Their examples were often limited to air war and land operations in Europe. The mentality of ‘bombing your way out of every foreign-policy problem’ was a cheap and easy solution for politicians who thought in neat political cycles. The first bloody half of the 20thcentury encouraged others to shape scholarship and political thought that Britain was to engage in dangerous continental commitments. This ignored, often purposefully, the broader experience of overstretched, over-committed, underfunded and poorly utilized resources such as land and air bases abroad that had, time and again, undermined national strategy and ignored all the available tools of the state to achieve national objectives.4 After 1945, many of these scholars had their own agendas, often rooted in a Service bias, which came with long-held heritage and baggage that directly and purposefully contradicted Corbett’s attempt to instil into British defence a culture of harnessing wisdom from experience, the result of which was to make high-level defence and national security decision-making easier. Instead, these scholars wanted to throw Corbett’s work on the bonfire of irrelevancy. As Corbett feared, reactionary responses needed to be tempered, and an intellectual approach maintained regardless of the pressures from above, something that excessive manipulation of ‘Jointness’ and ‘unification’ made difficult to protect and even harder to educate the military officer to understand.

1945-1966 was the Royal Navy’s greatest peacetime challenge. Although, initially, the experience of total war shook political and military decision-makers that maintaining the peace and not overstretching Britain’s resources to the point of collapse again was reflected in policy. In 1948, Prime Minister Clement Atlee repeated Admiralty warnings in response to suggestions for significant commitments to mainland Europe and that defence resources should be used wisely:

“…previous experience had shown how continental commitments, initially small, were apt to grow into very large ones.”5

Britain’s changing fortunes, some an outcome of two total wars, and the end of Empire, resulted in maritime voices arguing that it was possible to maintain support for European Allies and exert global influence. However, this only worked if fundamental realities about Britain’s position and vulnerabilities remained protected by policy. The developments in Britain’s so called ‘East of Suez withdrawal’ which led to the 1957 Defence Review was a series of opportunities to revisit national strategy. Instead, they became reactionary responses which under the surface were lacklustre, driven by budgetary constraints and Service rivalries where the ever-evolving nature of technology – missiles, information and sensors – dominated proceedings.

Instead, as is well documented, Britain would take a different course by the 1960s. As a result, the Admiralty’s well-laid plans, developed after 1945 and pioneered by 1SL Casper John (1903-1984), were broken by 1966, while Britain’s cultural and global connections were thrown away.

The fear of a threat and false apprehension of invasion – the Soviet at the door – was a classic argument to drive an agenda towards continentalism, one seen in Britain before and often driven with an anti-naval sentiment behind it. As the post-war decades went on, many viewed navies in terms of ‘fall and decline’ – considered outdated, irrelevant, imperial and useless to national defence. The Royal Navy after 1966 became a subservient adjunct to the U.S. Navy and American foreign policy, confined to Anti-Submarine Warfare operations in the North Atlantic. The United States drove concepts for ‘maritime strategy’ in the 1980s, but it was little more than glorified ‘naval strategy’ as American navalists attempted to finally close the struggle they had endured after 1947 to justify the massive investment to the U.S. Navy for a continental nation. Navies were no longer seen as instruments for maintaining the peace, and other tasks were deprioritised in favour of land-focused concepts. This was demonstrated in fake terms such as ‘warfighting’ that revealed the rejection of an entirely British model that had developed over generations.6 It was a far cry from even the start of the Second World War, where British war efforts were at least somewhat Corbettian. Importing American ideas – Prussian, German and land-based – and extended land commitments with ‘air power’ destroyed Corbett’s influence. Understanding of his work faded by 1981.

The irony is that awareness of Corbett, his work, and, more importantly, why and how he had gone about his work, was undermined by a Naval officer: Lord Louis Mountbatten (1900-1979). As mentioned earlier, in 1921 Corbett was concerned that the Naval officer was ill-equipped for specific tasks, especially in Whitehall. As Corbett had warned, intellectualism and education were part of having an advantage over an enemy – something he demonstrated by pointing out the consistent trend in the most successful British Naval leaders – considering that Britain was, resource-wise, always on the backfoot. Future officers needed to be trained to think about problems by working through past experience to answer them and be aware of the new technologies and influences that were taking place. Instead, Lord Mountbatten, Air Marshal John Slessor (1897-1979) – representing the extremist wing of Air Marshal Trenchard’s (1873-1956) prodigy – and Army leadership could not see past the short-term tactical experience of the Second World War. Their agendas and vested interests often overrode the national interest. The political appetite for the uncertainty this bought towards creating sound and stable policy that evolved as needed was all the motivation politicians required to force greater control over the British armed forces.

Reactionary responses in the short term effectively threw away national experience and instilled in civilian leadership, and the military alike, that history had little to offer them. Alongside defence unification, the seeding of these attitudes, repeated in professional military education, was that studying history and making strategy ‘was too difficult or controversial’. This was a view that the political classes shared not just because they no longer had mechanisms to understand strategy entirely, but from their perspective, it seemed no one could ever agree on strategy or defence policy, so defence was seen as ‘out of control’. This only proved what Corbett had done and why. It sealed the end of the influence of Corbett, after his death, in terms of British defence and national security. ‘Jointness’ was bruited as a convenient stop-gap, supposedly superior to strategy because it made decision-making for the political and military classes easier and avoided the embarrassment of squabbling between the Services as their budgets were ever tightened. Educating political leadership on national strategy was lost to time, and, combined with the unification process, it was the ultimate and lasting insult to Corbett.

In reality, the common belief that the objective of superior British strategy drove Mountbatten or British unification has no factual basis. As the history of unified defence departments show, permanent turmoil and distress are no foundation for organisational success. Moreover, there are rare examples in history where such drastic changes in the structure of a well-established organisation, central to national culture and policy – the Admiralty’s institutional experience was greater than that of the British Parliament or the War Office and Air Ministry combined – could recover from such traumatic and fundamental change. That is not to say that the Royal Navy failed the tasks placed upon it after 1964; it remained a competent, successful and doctrinal led professional fighting Service, but the state no longer understood what maritime strategy had to offer and how superior it was to the new continentalist status quo.7

The limited revival of Corbett occurred at a moment in which the sudden shock that history does not follow a linear path was demonstrated by the 1982 Falklands War, a war which was to be maritime and Naval-led. The fact that British defence policy up to 1981 was exposed for what it was – a continentalist’s fantasy, alien to British experience – did more for Corbett’s legacy than the Falklands campaign itself. This was not because Operation CORPORATE was a significant achievement in the truest sense of the Naval Service but that it made the point that it was nigh impossible for Britain to focus just on Europe or that history would be so easily swayed from the trends of the past. In the decades that followed, the work to bring Corbett back into academic, political and historical studies had begun. The task was to ascend his work from the purposeful box he had been placed in after 1945 by those who did not want to address uncomfortable questions. It is always better to debate challenges and problems than to retreat to well-trodden, comfortable, safe havens that serve nothing more than to reinforce and stagnate the intellectual capacity of those involved with national defence.

The maritime doctrine that resulted in the form of BR18068 by the mid-1990s demonstrated that rebuilding the intellectual world-leading excellence of British strategic and maritime thought was still in its infancy. It was an emergency band-aid in an attempt to reignite and update Corbett’s primer for maritime strategy for military personnel, Some Principles of Maritime Strategy,9 into something useful for a latter 20th-century military professional reader. Yet it remained far from utilising the Falklands War or Corbett to return to the point of serious discussion on national strategy. Instead, what was needed was that Corbett not be viewed just as a naval historian but elevated to his rightful place as a strategist and thinker amongst the greats.

For island nations, the future of defence policy by maritime strategy in a more comprehensive national strategy remains vital. Continental countries rightfully think in continental terms for foreign policy, who can pick and choose their strategy and policy, while island nations have unyielding concerns to worry about, such as their energy and food security. The battle to educate why and about maritime strategy remains a problem, one Corbett understood.

The advancement of new elements of theoretical maritime strategy for all nations can be found in space and strategic space policy. Many key tenants can be found in Corbett’s Some Principals as applied to space policy. Thesecan be easily made evident by how space influences what happens across Earth’s surface, yet it does not dominate it.10 Some argue that maritime views of space are irrelevant because they are based on ‘sea control’ and are an excuse to retreat to the post-1945 comfortable battlegrounds of interservice rivalry. The childish view that domains are the purview of but one service is a struggle not too unfamiliar to arguments that saw navies and air forces argue against one another in the post-war decades. It can be easily demonstrated today by air power theorists’ view that as space is ‘above air’ only their service can speak on it. Space has become further militarised, even as humans view the final frontier as a place of exploration. Yet it is increasingly from a military point of view about air power theorists reinventing themselves and propping up old arguments that won’t stand up to scrutiny. This was something navies had to do in the age of Cold War nuclear brinksmanship, until technology addressed deficiencies in warships exposed over the course of 1939-1945.

There is no blank cheque for theorists who accepted short-term tactical experience as the road to superior strategy as occurred in the decades after 1945 – increasingly exposed as providing few answers to contemporary problems. Debate entails a healthy exchange of ideas, some of which will challenge existing work and the status quo. Nevertheless, as ever post-1945, the sentimentality and affliction for immediate service needs over the needs and realities of national strategy remains true, something Corbett would have found abhorrent. He would have found them a ridiculous distraction and deflection as it only made the political establishment and Treasury further empowered to strip the military of what little influence remained for them to debate national defence policy.

To some degree, Corbett’s legacy and influence on the 21st century will remain problematic – if the conversation about him and his work remains one of navies, naval technology and naval operations. Nevertheless, Corbett offered an essential piece of wisdom that can be found as a thread across his work, useful to the civilian decision-maker and military officer alike. Corbett’s work was never a question of interservice bickering, nor was he just a product of his time, nor reflected Britain as an Empire or the nuances of Naval policy, but inescapable facts about Britain and its strategic experience that have timeless resonance. Thinking, pre-empting instead of being reactionary, deterring rather than fighting, and educating rather than guessing are key takeaways from Corbett’s studies. Only by studying history can skills and methodology be deployed to create an intellectual edge that the British Armed Forces will need in the future; the technological advantage is only part of the picture.

The task of building up the ‘thinking side’ of the military and Navy requires consistent investment. To embrace Corbett is to argue that Britain must retake the intellectual superiority and advantage over any other nation, and the Royal Navy is a fitting place to start. The message of intellectual development and education remains central to why Corbett remains relevant to those in defence and national security today.

Corbett used the past to think about the future; he demonstrated the ultimate combination of historian and futurist. Something that today we can replicate as we feel increasingly disconnected from times long gone. Yet, it can often be found that wasting time and resources by revisiting, repeating or reinventing things that are already easy to grasp and use to ‘get the job done’ today and tomorrow can be found in history. Corbett’s wisdom, in its unassuming form, is that it provides the example to reject calls that history is irrelevant; after all, experience is all we have and freely available to harness guidance from, rather than running the tightrope of relearning the costly and hard way, with all the associated risks involved.

Andrew Lambert, 21st Century Corbett: Maritime Strategy and Naval Policy for the Modern Era, 21st Century Foundations (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2017).

Andrew Lambert, The British Way of War, Julian Corbett and the Battle for a National Strategy (Great Britain: Yale University Press, 2021)

James W.E. Smith, “Deconstructing the Seapower State: Britain, American and Defence Unification,” PhD Thesis (King’s College London, 2021).

Michael Howard. The Continental Commitment, the Dilemma of British Defence Policy in the Era of the 2 World Wars; the Ford Lectures in the University of Oxford 1971. London: Temple Smith, 1972.

“Deconstructing the Seapower State: Britain, American and Defence Unification,” p. 90.

The term ‘warfighting’ does not exist in the Oxford Dictionary. The term became popular in the late 20th century in the United States who were embracing German General Staff principles from the Second World War.

“Deconstructing the Seapower State: Britain, American and Defence Unification,” p. 78.

HMSO. The Fundamentals of British Maritime Doctrine: BR1806. 1st ed. London: HMSO, 1995.

Corbett, Julian. Some Principals of Maritime Strategy, edited by Ranft, Bryan. 1972 Impression ed. Greenwich London: Conway, 1972.

Smith, James W.E. “Corbett offers more on Space than Mitchell.” War on the Rocks, 11 Dec. 2019.